Researchers at the University of British Columbia recently published findings in the journal Neuron from a study on the first mutation explaining development of multiple sclerosis (MS). Researchers have long found MS to run in families, but the exact genomic locus of the disease has remained elusive.

Researchers at the University of British Columbia recently published findings in the journal Neuron from a study on the first mutation explaining development of multiple sclerosis (MS). Researchers have long found MS to run in families, but the exact genomic locus of the disease has remained elusive.

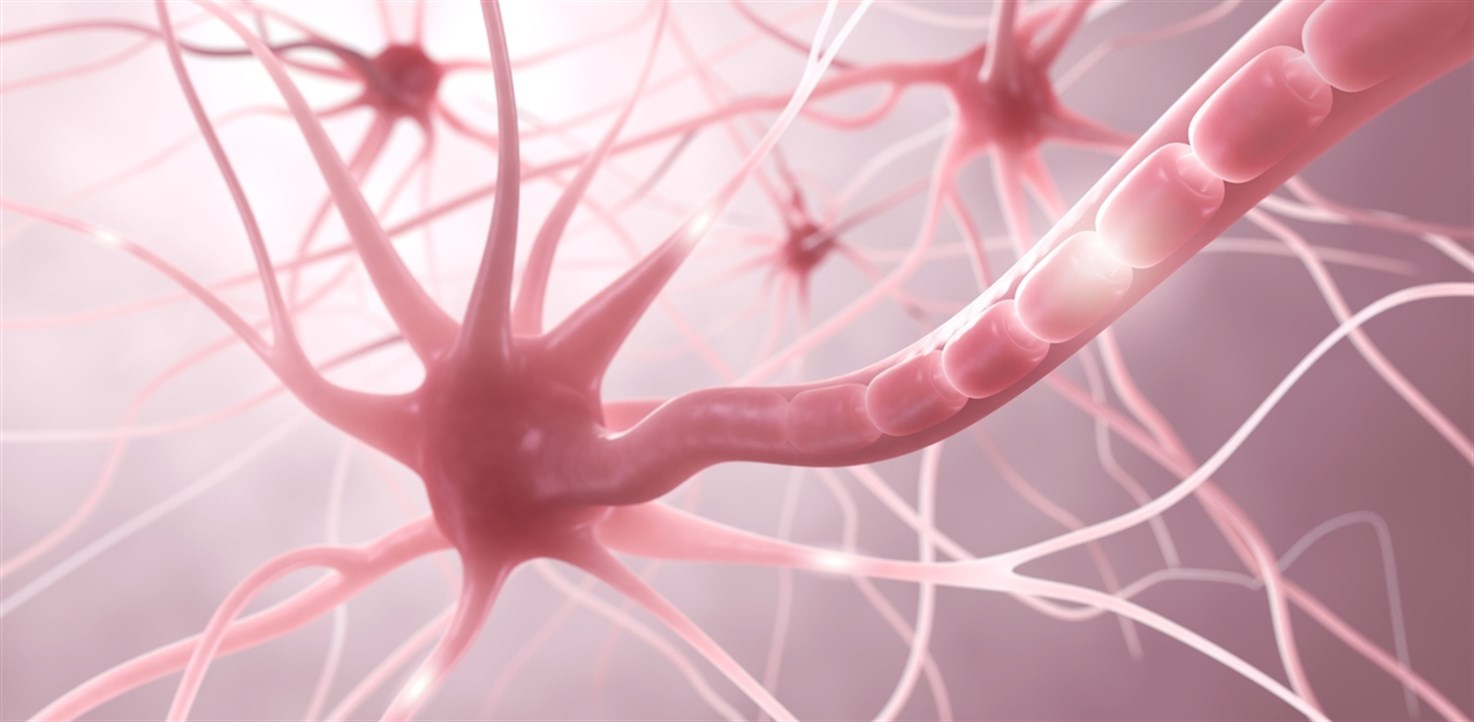

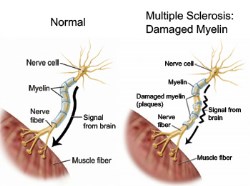

In patients with MS, the immune system destroys the insulating myelin sheath around neurons, which upsets the conduction of electrical signals throughout the nervous system. This deteriorates the nervous system’s ability to communicate throughout the body, leading to various effects including possible pain, tingling, and numbness in the limbs, blurry vision, and impaired hearing.

Researchers know that about 10-15% of MS cases have a hereditary component, but until now, few gene variants have correlated with increased risk of developing MS. By contrast, people with the gene mutation studied by the UBC researchers have a 70% chance of developing the disease.

The researchers carried out the study by reviewing materials from the Canadian Collaborative Project on Genetic Susceptibility to MS, a large database with genomic information from over 2,000 Canadian families. They looked for rare coding mutations in families with multiple occurrences of the disease and cross-referenced their findings with the genetic information from other families with multiple occurrences.

The missense mutation, a mutation that makes the gene code a non-functional protein, is in the NR1H3 gene. NR1H3 codes for protein LXRA, which controls transcriptional regulation of genes involved in lipid homeostasis, inflammation, and innate immunity. Mice without the NR1H3 gene tend to have neurological problems, including a decrease in myelin production.

Researchers contend that the discovery of this mutation will allow them to create cellular and animal models for MS that are physiologically relevant to the human disease – tools which have not been previously available.

For more information: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/06/160601132134.htm